Mavis Mitchell

Footscray Hospital’s first nursing director from 1952–1970

Mavis Mitchell trained as a nurse at the Royal Melbourne Hospital in the 1930s before travelling to Britain as a young woman to continue her nursing career. She served with the British Army’s nursing service during World War Two.

After the war ended she returned to Melbourne and worked at the Alfred Hospital and Williamstown Hospital. In 1952 she was appointed Matron of the soon-to-be-opened Footscray Hospital and established the general nurse training school at the hospital.

A nursing scholarship - the Mavis Mitchell Memorial Scholarship - and the Mavis Mitchell Room at Footscray Hospital were named in honour of her achievements as a leader and educator.

Matron Mavis Mitchell.

Western Health archives

John Thomson, surgeon at Footscray 1955-1993: “Matron Mitchell was the leader of the band. She was the boss. She had panache. She was a commanding, magnetic individual who was just and reasonable.

She had a quick, analytical mind and unflagging energy. The leadership lessons she learnt during her period of war service played an important part in her administrative leadership in nursing.”

Joseph Epstein, junior medical officer and later surgeon at Footscray Hospital 1963–present: “Mavis Mitchell was a remarkable person. She knew everyone. She was also great fun. At Christmas time she wanted to give all the children in the hospital a thrill. So she arranged for me to dress up as Father Christmas and land in a helicopter on the lawn.

You can’t land a helicopter on the lawn of a hospital unless it’s an emergency. But Mavis knew somebody in the Civil Aviation Authority and managed to get permission.

I remember when concerns were raised by a staff member that some of the junior residents might have been going upstairs and fraternizing with the nurses. Mavis’s attitude was very sophisticated about such things. She just said, ‘Not my doctors, they don’t misbehave’.”

Liz Edmonds, nurse, nursing administrator at Footscray Hospital 1960 – present: “In the ‘60s, the hospital gardens were lovely and you would often see rabbits hopping around. Mavis Mitchell had a cottage at the end of the garden.

She was a very imposing lady and we had huge respect for her. You had to stand in her presence.

We all ate our meals in the dining room. The tables were set with white linen tablecloths, silver cutlery and you were served by waiters. Matron Mitchell had a particular table in the room off to one side. You had to stand at the door of the dining room until she acknowledged your presence and then you could go in.”

Elizabeth McNeilage

Theatre nurse and manager at Footscray Hospital from 1964–1976

Theatre supervisor Sister Elizabeth McNeilage,(right) with her student Carol Williams, winner of the J T Heuston Theatre Prize.

Western Health archives

Sister Elizabeth McNeilage was renowned as one of Victoria’s most effective theatre managers and nurse educators.

She was a British nurse who came to Melbourne after World War Two.

In Britain in 1938 she worked with Sir Howard Florey’s team at the John Radcliffe Infirmary at Oxford when the team was developing penicillin. She also assisted in pioneer chest surgery at Brompton Chest Hospital.

In Melbourne, before being appointed to Footscray, Sister McNeilage worked with the Australian surgeon Sir James Officer-Brown, who was carrying out the first operations on “blue babies” – infants with congenital heart defects.

Kevin King, surgeon at Footscray Hospital from 1964-1985: “Sister McNeilage had worked at Oxford in the neuro-surgical theatres before she came to Footscray. She was a rather plain, mousy looking woman but she had an extraordinary formidable personality.

She was the only person I ever saw Kendall Francis apologise to when he arrived late for theatre. She never, ever said anything nasty to anyone but if you were late for an operating list, even by five minutes, she’d be in the corridor.

She wouldn’t be standing with arms akimbo but she’d be standing behind a pillar and what was being unsaid was, ‘My nursing staff were here an hour ago, the theatres are all set up, where the hell have you been?’

Her theatres ran like clockwork, her staff were devoted to her and, as is often the case, it was like being in an elite unit in the army during the war.

Nursing staff were worked into the ground by certain surgeons who were not too considerate but she always protected her nurses and they thought she was marvellous.

She was the only person I met in the hospital context, particularly in the inevitable collisions in the corridors between surgeons demanding theatres with good reasons, who would make a decision and say, ‘I think this is in the best interests of the patient’ and that was it. People would back off. We took her advice because we had enormous respect for her.

There’s no one in the hospital system, here, or in England, that I had such unparalleled admiration for. One of the great regrets of my life is that by the time I’d finished at Footscray there were a lot of us around who thought the world of her. We should have tried to get her some recognition. If anyone deserved an AO (Order of Australia) it was her.”

Beverly Howard, student nurse and theatre nurse at Footscray Hospital from 1966–present: “She was lovingly called Mother McNeilage by her staff. She looked after you like a mother would. She was strict but she cared for her charges like a mother duck with her ducklings. The surgeons had the same respect for her as her nurses did.”

David Kennedy, urologist, Footscray Hospital 1960s–1990s: “I first met Sister McNeilage when I was a student at the Alfred Hospital. She came out from London to work at the Alfred’s cardio-thoracic theatre with Sir James (Jim) Officer-Brown, a pioneer in heart surgery.

She had been trained in strict English conditions. I remember telling her one day that I wouldn’t be in the following week because I was going to play golf. She looked at me and said: ‘Who do you think you are?’

She was very strong on discipline – she lived quite a distance away on the other side of the city and she used to get the train each day to get to the Western before 8am, which was when we started our operating list.”

Alison Garven

Footscray hospital’s first pathologist, from 1955–1983

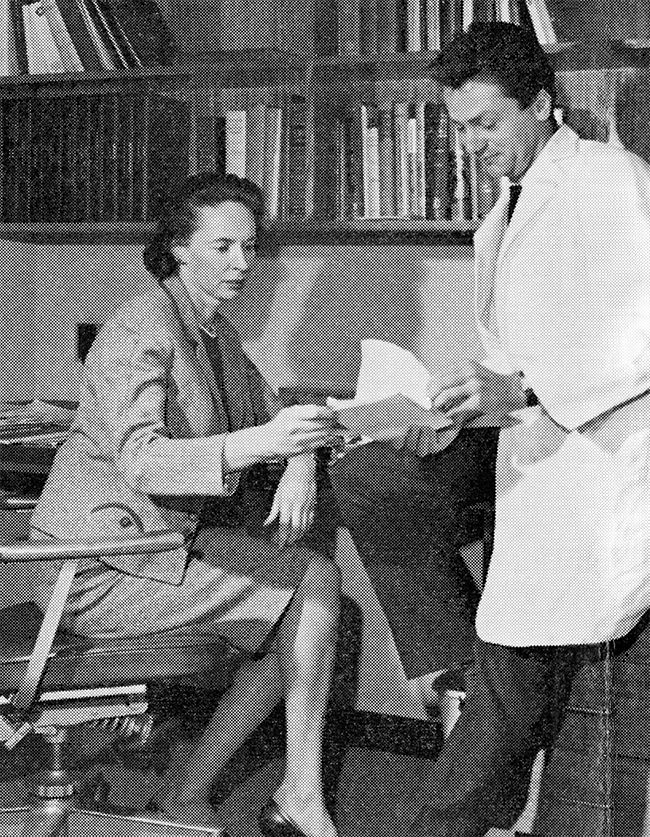

Pathologist Alison Garven discusses a case with pathology registrar Dr Peter Rose in 1966.

Western Health archives

Appointed in 1955, Dr Garven was a rarity in the 1950s and 1960s – a senior female member of the medical staff employed on a salary at the hospital. In 1983, she retired as director of pathology after almost 30 years’ service to the hospital.

Joseph Epstein, junior medical officer and later surgeon at Footscray Hospital 1963–present: “Alison ran the pathology department on a shoestring because the hospital was always short of funds.

She was a wonderful teacher and ran a very good, reliable pathology department. She hired a laboratory manager Mr Booth. He developed a lot of the technology that Alison used in her department.

We didn’t have any money for a clinical photographer so Mr Booth used to do it. Alison was very astute and was able to garner support from a lot of non-medical people.”